Ocean loaders. Zzap64. Cassette Tapes. Budget games. These are the first images that pop into my head whenever I think of the Commodore 64. Why? Because I’m from the United Kingdom, one of the heartlands of the C64. But what about someone from one of its other stomping grounds, such as the United States and Canada? What are their mental images of Commodore’s 8-bit wonder?

A Eurocentric Perspective

Most C64 enthusiasts I’ve rubbed shoulders with over the last several years have been European, specifically from the UK. As the most numerous and vocal, the scene and history of the C64 in the United Kingdom feels the most visible to me. But since joining BlueSky, I’ve seen more US folks share memories of growing up with a C64 and express their love for it. There has also been a recent wave of YouTube shorts creators from North America showcasing the C64. It’s only made me want to learn more about this aspect of a computer near and dear to my heart.

I will admit to having a Eurocentric perspective for the longest time. Even now, when I think of ‘European home/microcomputers,’ I have to stop myself from neatly slotting in the C64 and Amiga alongside the likes of the ZX Spectrum, Dragon 32, and Amstrad CPC. Why? It does feel like we claimed them as our own, keeping them alive and well-supported into the early 90s. But the Commodore 64 is an American computer. There is a rich history of its life stateside with avenues in business and education it wiggled into that simply didn’t happen on the same scale or at all in Europe. A place of importance in the stories of some of the biggest developers and publishers in the industry, past and present that gets overshadowed by the region’s own NES-centric pop culture video game histories.

Let’s begin our journey by taking a look at something that set the Commodore 64 apart from its rivals also vying for dominance of the home computer market in North America.

The Price Advantage That Sold Millions

The Commodore 64 occupies a place in the Guinness Book of World Records as the greatest-selling single computer model of all time. Now, early on, it was always a wee bit nebulous when it came to C64 and Amiga sales. Jack Tramiel boasted of selling twenty-two to thirty million Commodore 64s by extrapolating his claim of selling 500,000 C64s a month (likely closer to 200,000) during his time helming the company. Most sources put it at around 17 million. But in 2011, this site here did some hard analysis and arrived at a figure of 12.5 million. Of these, Europe accounts for only 4.5 million. And although I haven’t been able to pin down an exact figure, I think it’s safe to say that North America accounts for the lion’s share of the remaining given that in its first year of sales, 1982-1983 Commodore sold two million C64s, a staggering amount for the time and outselling all competitors such as the Apple II. That’s upward of seven million North American Commodore 64 owners, five times that of the United Kingdom.

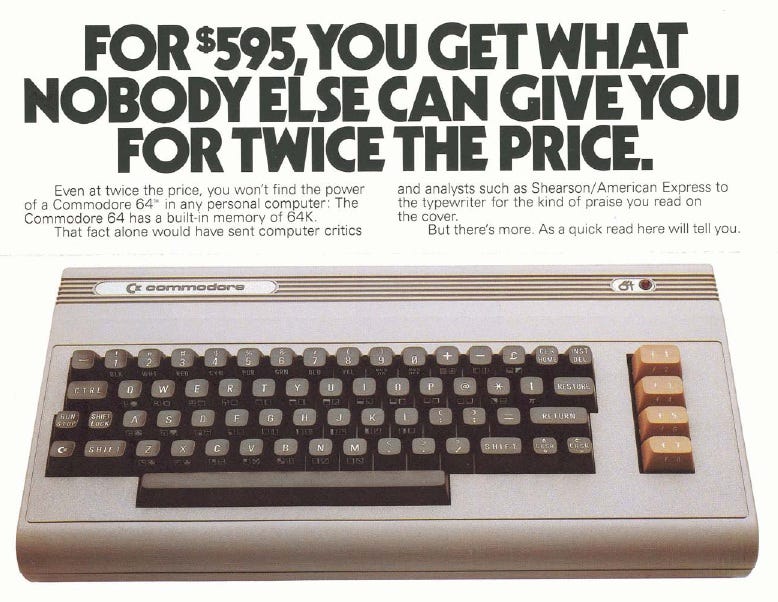

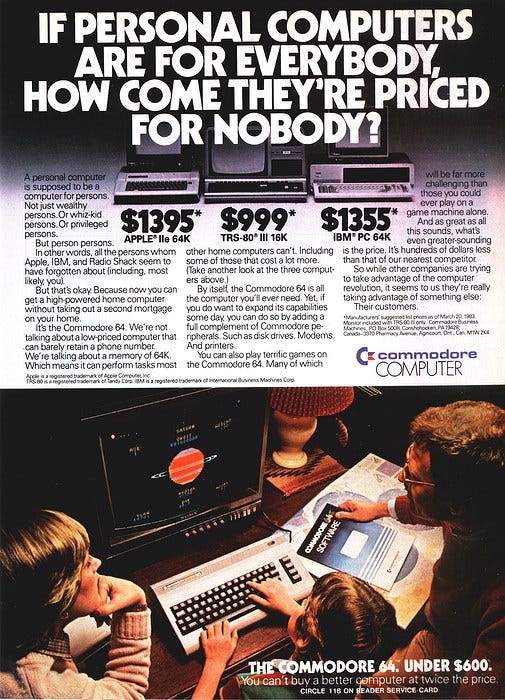

Looking at the ads above and below, we can see the reason for this runaway success: the Commodore 64 gave you a lot of bang for comparatively not all that many bucks. $595 (a price that would drop to $199 by 1988) put the computer within reach of the families and small businesses that couldn’t afford the $1395 that Apple was asking for the Apple IIa and $1355 IBM asked for its own lower-end PC, all while offering superior sound and graphics. Apple attempted to counter with the IIc in 1984 but then then it lacked much of what the Commodore 64 offered right out of the box and was priced at $1295. Never did Commodore’s tagline in the ad below ring truer.

A Question of Formats

Let’s address the elephant in the room that adds context to why distinct software scenes emerged between North America and Europe: software format. While Europe’s Commodore 64 software scene was dominated by cassette tape, North America’s format of choice was the 5 and a 1/4 inch floppy disk. The big ol’ things that wibble-wobble when you wave one about like a sheet of paper.

This dramatically changes the landscape of the kind of computer games and productivity/business software you can offer your user base when you factor in the differing storage capacities. A single side of audio tape would generally hold a hundred kilobytes of data and well, you sometimes have to cross your fingers and hope they load it correctly. Floppy disks, while loading surprisingly slowly without a Fastload cart used in tandem, held almost twice that amount of data per side as a minimum. They were also more reliable. Those publishing software on floppy disks also seemed more willing to span multiple disks, leading to larger programs and games. This presents a problem when you want to sell software in both North America and Europe; not all games can be crammed down to fit on a single tape.

European 8 and 16-bit era folks will likely be aware of US Gold. Based in Birmingham in the UK, this company specialized in bringing ‘The best of All-American Software’ from the US to Europe – complete with its own loading screen fanfare. But it would be more accurate to also say ‘What We Can Find That Will Fit on Tape’. With a focus on arcade conversions and smaller action games, this too would have coloured the perception of what the American C64 scene was like. On the surface, given the kind of games that US Gold released, it wouldn’t have seemed all that different.

While researching info for this article, I found a lovely post from 2009 on a thread discussing the different markets on Lemon64 from someone active in the software scene during this time. It adds some important information and context so will share most of it here.

As I am from London, England, but travelled extensively around the U.S. in the mid 80’s to late 90’s, I think I have a broad understanding of the markets.

It is absolutely true that American’s being richer, did tend to have Apple’s and Pet’s as their fi(r)st computer, not Vic-20’s, C64’s, Spectrum’s, Oric’s and Amstrad’s etc, like we had as our first computers in Europe. These Apple’s and PET’s, although having some games were purchased for home accounting and newsletter production (1 in 3 Americans ran some sort of newsletter back then!)

Unlike the European first computers which,being tape based, were not really suitable for business use and were geared much more to games machines.

When American’s started buying Vic-20’s and Commodore 64’s, they bought them with floppy drives from the get-go. As gamer’s we noticed this by virtue of Vic-20 American games that nearly all needed memory expansion, and of course those American C64 games, like the Infocom titles, etc, that were only available on floppy.

With Europe being tape based and American being disk based, the two markets were very different even in the games arena. American developer’s didn’t produce arcade games like European tape based games, (which were nearly all some form of arcade game, maze or platform) after about 1983. If you look at the pure arcade games that are American, you find them to be 83-84 releases. Starting in mid 84 the American market just imported Arcade games from Europe, just like at that time if you wanted an Infocom title you needed to import it.

There was a period of time, as I am sure you remember, where you could get a U.S. gold multi-load tape game, but if you wanted the disk game you had to buy an import copy!

This difference meant that in America, an arcade game wasn’t a sideways scroller shoot’em up, like Parallax, for them an Arcade game would be Rescue on Fractulas, or Ghostbusters. Even Elite, being ‘arcade based’ did not have the impact in the U.S. as it did in the UK.

In addition, with American gamers almost all having 1541’s it meant they demanded games that utilized their hardware. This meant that American publisher’s had to start thinking about utilizing the floppy. By late 84 we started seeing games like Ace of Aces or Silent Service that were totally different from what UK/European C64 developers were working on. Many many gamers, while knowing of titles like Zak McKraken, would not play the game at all until the late 90’s when emulation came along.

Because the American 64’s had floppies, they were also used for business too. They were in American schools too. This meant that American gaming magazines had to cover a much wider range of software and hardware. From printer’s to educational software and all the associate software to go with that. It’s for this reason, for example, that the U.S. never had the equivalent of the UK’s Zzap 64.

By the late 80’s the C64 was beginning to die in the U.S., while still going strong in the UK/Europe. What revitalised the U.S. market was licensing and those same UK arcade game’s. American Gamer’s knew nothing of games like Armalyte and Parallax. In 1989, for example, I came over with Firebird executives to the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show, a trade show for everything electronic. The next year they opened a U.S. office in NJ and America discovered Bubble Bobble, etc! Mastertronic also started up (in California, I believe) and American’s discovered C64 games for $9.99 instead of $39.99! Between the UK arcade titles breathing new life into the C64 games market you also had the start of licensed games becoming the thing in the U.S. market..

So in conclusion, the American market has been very different to the UK market. While 90% of Europeans were playing games like The Last Ninja and Summer Games, American’s were playing Pirates and Seven Cities of Gold. We were all playing games, but one market hated joystick waggling and the other loved it!!!

So it went with the magazines. We got Crash and Zzap and other ‘comic’ gaming mags and the American gamers got more serious magazines that included programming info and utilities and business software coverage just because their C64’s had a 1541 attached in practically all cases. There is an argument that America now drives the game market because of those more serious magazines back in the 80’s, with many more American gamers learning programming because of the much wider range of disk based utilities available that we weren’t interested in Europe with our tape based machines and our Zzap style magazines.

Credit to ‘Humorguy’ as this post does a lot of the heavy lifting I planned to do with pointing out key differences between North America and Europe. There’s definitely an aura of seriousness when it comes to the Commodore 64 software scene in North America of the 80s, lacking as it did the anarchic bedroom coders scene replete with European humour and crafted by teenagers to be sold for £1.99.

The emphasis on the longevity of the C64 in North America is also timely in the wake of watching this 1988 episode of the Computer Chronicles as part of my research. Here, it’s referred to as the ‘Model T of personal computers’ and is still being praised as a capable machine by one of its more ardent supporters: Electronic Arts. A user group also showcase how they still favour and use the computer for things other than video games. If you took just the most common popular awareness of late 80s North American video game history, you’d walk away believing that the NES had rescued video games, smashed away all the competition, and everyone played Mario or the Legend of Zelda. Not so much, if that big ol’ wall of C64 games at a Toys R Us is anything to go by and the growth in sales that Electronic Arts reports.

That last paragraph in Humorguy’s post is an important one for understanding just how important the C64 was stateside. It leads nicely onto something we’ll explore in part two: the C64 games North Americans played and the companies that made them.

The American computer game market developed into a more modern form of production before the European one did. Electronic Arts is the prime example – they built their entire company on the success of their games for the Commodore 64 before moving to consoles. By the time the home computer market crashed due to the Commodore price war, publishers in the US were no longer doing one-person developed games (with exceptions like Jordan Mechner). Volume was not as important as quality and the audience tended to be older than the pre-teens or early teens in the UK, so they were producing less arcade style games (though arcade ports did have a very big audience).

LikeLiked by 1 person