I’ve been looking forward to sitting down and tapping this feature out, part one of two, as it has been such a fascinating rabbit hole to go down. One infused with Y2K-era optimism – and hubris.

Last week, I had another good dig around in a snazzy disc from 2000: a promotional CD distributed by Sony at the European Computer Trade Show. This industry event, held from 1988 to 2004, was one of the year’s marquee events. A chance for all the makers and shakers in the video game and computer technology industries to showcase what they’re up to. As the millennium dawned, it turned out that Sony had some big plans to not only introduce the next generation of PlayStation console but to also change the nature of entertainment forever: The Emotion Engine.

Let’s see what Sony had in mind in its own words from the ECTS disc press release:

NEW ORLEANS, July 24, 2000 – Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) announced today its strategic vision for the evolution of computer entertainment in the broadband network era. Just as the PlayStation 2 computer entertainment system ushered in a new era of consumer-based computer entertainment, the company looks to escalate the evolution of digital cinema and high definition content development through a real-time development system designed for a broadband network environment. This system will provide the world’s greatest content creators in film, TV broadcast and interactive entertainment access to a new community for digital creation and distribution.

Continuing to illustrate its role as an entertainment visionary, the company will unveil real-time technology demonstrations with leading strategic partners in the areas of content creation, servers, video, sound and middleware to drive future broadband experience in computer entertainment and e-cinema, the future of in-theater entertainment through a broadband network. Key demonstrations will be conducted during SIGGRAPH 2000 expo, the leading international conference on computer graphics (CG) and interactive techniques, held July 25-27 in New Orleans.

Note their use of the term computer entertainment system instead of game console. I’ve showcased on social media several times over the last few years (and that’s what part two will be about) just how wide-ranging Sony’s plans for the PlayStation 2 were. It wouldn’t be just a games console; it would be an entertainment hub. And I’m not just talking about the DVD player here; Sony’s plans were for an unparalleled level of connectivity that far exceeds Microsoft’s with the original Xbox One. Not only would you hook up your TV, but also your laptop, your phone, your internet connection – and mouse and keyboard. The PlayStation 2, through the power of Linux, would replace the need for a separate desktop PC. You’d browse the web, play online games, and watch digital and physical movies; all forms of entertainment would revolve around your PlayStation 2.

Or so they hoped.

This Y2K optimism-fuelled dream existed only briefly. It was most prevalent in the run-up to the release of the PS2 and the first year of its life. Then Sony, just like Xbox post-2013, quietly swept away its unfulfilled ambitions and focused wholly on it being a home video game system first, except for the DVD movie-playing capability that had proven itself to be a system seller too.

But what about before then and outside of the home?

Enter the GSCube

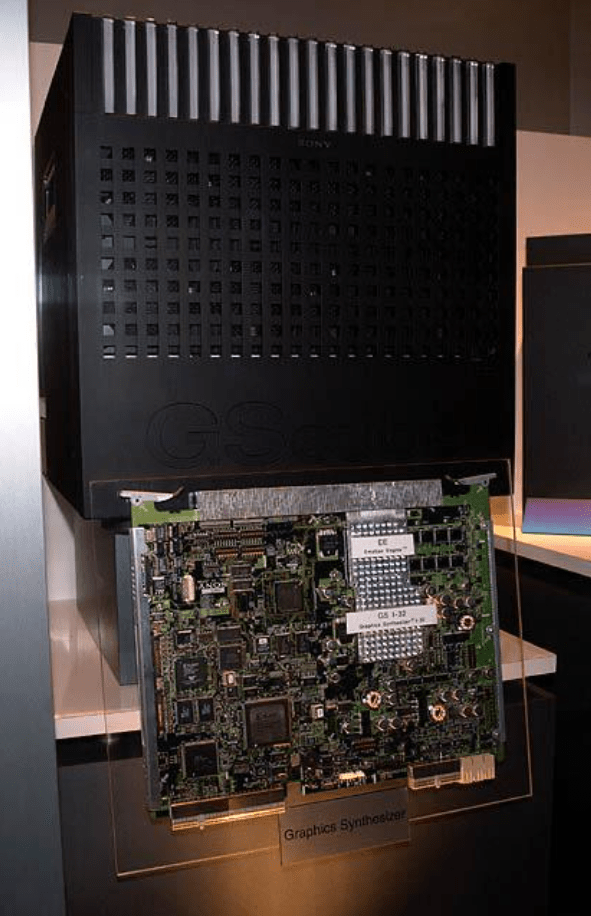

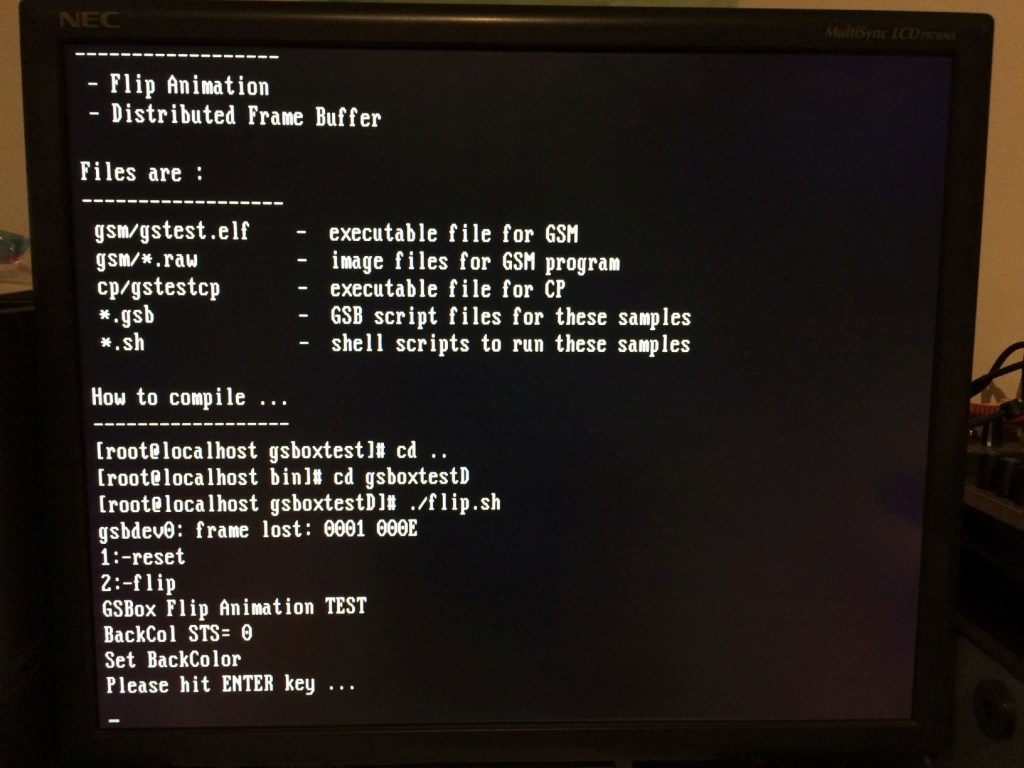

Sony describes the GSCube as a ‘graphics visualizer’ and was the successor to an earlier pre-PS2 prototype called GSBox demonstrated a year prior at Siggraph ’99.

Built around the guts of a PlayStation 2 (the Emotion Engine CPU and the Graphics Synthesiser GPU), the GSCube runs sixteen of its motherboards in parallel to form its beating heart, each of them sporting some additional oomph over the base PS2. The GPU of the PlayStation 2 contained just 4MB of embedded graphics memory (VRAM) which, in comparison to PC graphics cards of the time and even the Dreamcast, was relatively small. Other elements of its architecture, fast frame and texture buffers, attempted to compensate for this limitation. Now, for what they had in mind, a paltry amount of VRAM wasn’t going to cut it, so Sony upped the graphics memory to a roomy-in-comparison 32MB. This Frankenstein creation would wield 2GB of DRDRAM, 97.5 Gigaflops of FPU performance, 512MB of eDRAM, a Pixel Fill Rate of 37.7 GB/s, and 16 x 294mhz of processor grunt power – hefty on paper and something Sony was excited to demonstrate in action at that year’s SIGGRAPH.

Early Excitement

Once they brought it to life, Sony are stoked about their new baby. Let’s hear just how much from the father of the PlayStation himself, Ken Kutaragi.

“As Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. fused the technology of computers and the world of entertainment to create and evolve a new market called ‘Computer Entertainment,’ we are now pioneering the creation of real-time digital entertainment through an extension of the technology of the PlayStation 2 computer entertainment system,” said Ken Kutaragi, president and chief executive officer, Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. “At SIGGRAPH 2000 we are unveiling a development system that will enable conventional and traditional content creators to realize new methods to communicate storylines and experiences through the digital network environment. We embrace the software development communities and hope that together, we can usher in the future of entertainment currently not realized through existing technologies.”

There is a lot to unpack here. An evolving new market called Computer Entertainment? Real-time digital entertainment? Content creators? The digital network environment?

It’s amazing to see things you’d expect to hear today being used almost twenty-five years ago. Especially the term ‘content creators’. But yes, let us next home in on real-time digital entertainment as it really is the heart of the matter.

Virtual Idols in Real Time

Sony had ambitions for GSCube and the PlayStation 2 in what it termed the ‘Broadband Era’. One of these was ‘e-cinema’ and again, I’ll turn to Sony’s press release to explain their thinking behind this buzzword.

SIGGRAPH 2000 “E-Cinema” Experience – Fusion of Games and Movies

The company’s booth at SIGGRAPH 2000 offers a glimpse of the framework for the future evolution of the networked digital entertainment market. This environment is divided into quadrants each demonstrating specific applications utilizing the GScube development system. These areas include the main theater, an advanced theater experience using a Digital Projection Inc. LIGHTNING 15sx projector based on core DLP technology by Texas Instruments, and a “backstage” technology area comprising of broadband network content production, distribution and an in-home experience through a “living room of the future” display. Some content will be demonstrated and viewed through a newly developed, 24-inch high-definition monitor that handles 1920 x 1080 resolution at 60 frames-per-second progressive scan. Sony Corporation designed this monitor for use in the high-end broadcasting and editing markets.

The fusion of games and movies. This was something that was heavily promoted both in the run-up to the PlayStation 2’s release and throughout 2000. It was something that Hideo Kojima was a big proponent of, too. The PlayStation 2, with its ‘Emotion’ Engine, would allow for graphics that were so realistic that characters could finally convey human-like facial expressions.

In some ways, it harkens back to the early 90s when full-motion-video games were seen as the wave of the future, that games were ‘more realistic’ and better simply because they employed live-action video rather than pixels or polygons. Except here, live-action is the redundant factor. In this new Emotion Engine-powered millennium, video games and movies as separate forms of entertainment in the home would eventually cease to be as the PS2 and GSCube technology matured, replaced by a fusion of the two, populated by virtual actors and scenes viewed in real-time and generated before our very eyes.

Generated in real-time? Virtual actors?

Reading through these press releases last week, I couldn’t help but be struck by a feeling of déjà vu. It’s eerily similar to some ambitions for generative AI, though it feels a lot less wrapped up in trying to cash in on a tech craze and rampant greed and more in Y2K futuristic optimism.

Let’s turn again to the press release:

This powerful architecture will initially provide 10 times the performance of the PlayStation 2 computer entertainment system, with future iterations of the technology potentially exceeding this 100 fold. The combination of the GScube and high-end broadband servers, such as the soon-to-be announced next generation SGI Origin series server, create an optimal environment for the creation, manufacturing and distribution of computer entertainment content, while charting the path towards realizing real-time generated e-cinema productions.

You can see why “The PlayStation 2 can do Toy Story in Real Time’ got bandied about at the time, though that may be an urban legend more correctly attributed to Bill Gates and Xbox. All that power behind the GSCube was intended for the real-time rendering of normally pre-rendered graphics.

The Sony Stars of SIGGRAPH

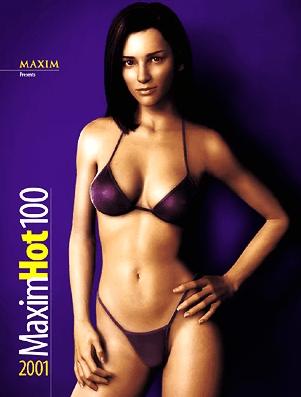

Sony pulled out all the stops at SIGGRAPH in 2000, demonstrating not only real-time rendered CG scenes from Antz but also The Matrix and Square’s upcoming blockbuster Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within – very much the poster child for the CG movie revolution and the perfect example for Sony.

Remember when Aki Ross made the Maxim Hot 100?

I couldn’t find any still images of the GSCube’s rendering of Aki Ross’s awakening, but I was able to do a comparison via footage of the SIGRAPH presentation and a clip of the movie.

We can see that the eyes, the eyelashes, the skin pores and the detailing are cruder compared to what we saw in the movie, but it’s important to note that this was being generated in real-time at 60 frames a second at 1080p, a task that would have crippled a single base PS2. Also key is that the GSCube didn’t do this alone, hence Sony’s terming it a Graphics Synthesizer and not a workstation in its own right. An SGI Origin 3000 served as the host, connecting the GSCube to a 64-bit PCI bus. Future models of the GSCube were planned to operate independently.

Reaction to the Siggraph presentation and Sony’s drive to bring aboard partners and adopters appears to have initially been positive. Along with the press release on the ECTS disc, there are also testimonials and statements of excitement and support for the new technologies. I’ll share a few of them.

“CG has taken a new direction. The ultimate goal has been to create photo-real 3D animation. With the newest advances in CG technology, that goal is now in reach. I believe artists will set new standards that challenge them to strive for an even higher quality of animation. As a creator, I am thrilled to see how far CG technology has advanced. It has allowed me to create what I have always envisioned.”

Hironobu Sakaguchi

Executive Vice President

Square Co., Ltd.

Chairman and CEO

Square USA, Inc.

“Square USA Honolulu Studio is currently producing ‘Final Fantasy,’ a full-length CG animation motion picture, to be released next summer. We have utilized the data used in the movie and rendered it in real time using the GScube, producing quality close to what is traditionally software rendered in about five hours. Our demo demonstrates features and effects usually reserved for non real time.”

Features & Effects

• Character’s expression created from deformation animation of high-quality polygons

• Individually drawn hairs

• Skin shader which realistically recreates human skin

• Background which utilizes radiosity effects

• Focus blur effect which occur in real-life camerasKazuyuki Hashimoto

Senior Vice President and CTO

Square USA, Inc.

“In our twenty years of producing computer animation we have always looked for breakthrough technology that has the potential to be accessed by a large audience. Sony Computer Entertainment has demonstrated the ability to scale consumer technology up to the forefront of the industry. The GScube has clearly shown us one exciting vision of the future of digital entertainment. With the help of Criterion Software, we have experimented with this new tool in our continue (sic) effort to explore new content production and delivery systems.”

Richard Chuang

Founder

PDI/DreamWorks

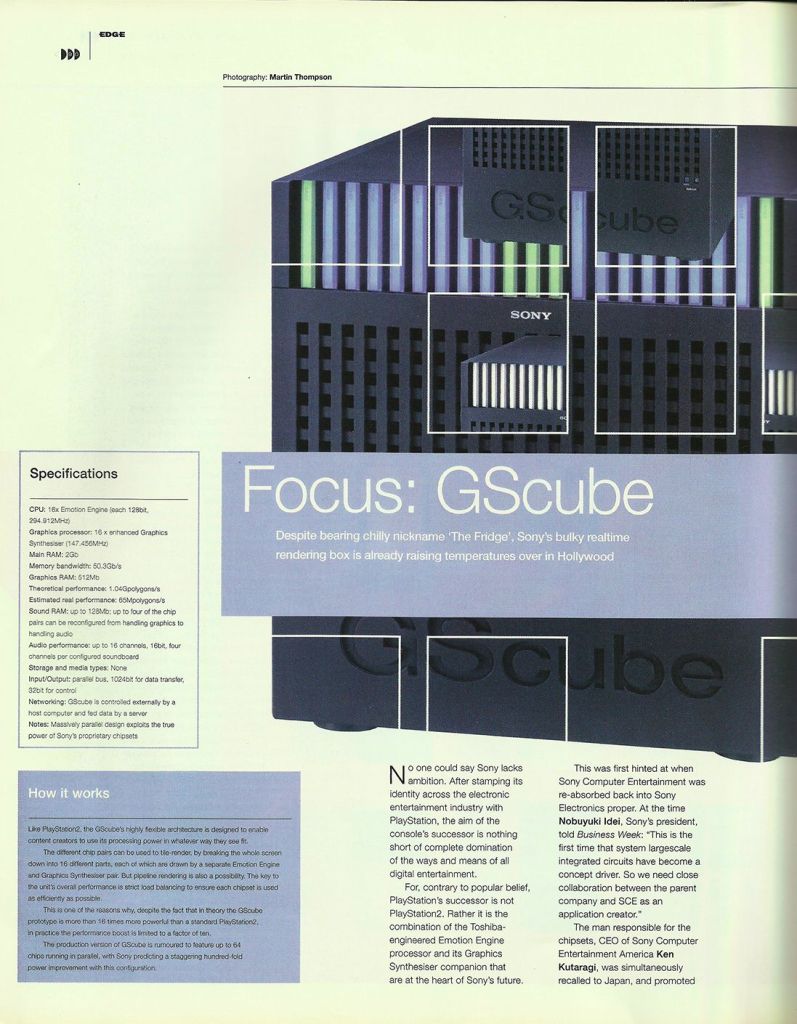

EDGE magazine, ever one to keep their fingers on the tech pulse, also went big with a feature on the GSCube.

It all looks, rosy, right? By the mid-2000s, we’ll all be watching e-cinema and browsing the web on our PlayStation 2s as new iterations of the GSCube bring real-time virtual idols to life before our eyes with even greater clarity as games and movies experience that fusion. And Sony will be the king of the entertainment world.

Right?

Farewell, GSCube. We hardly knew ye.

Well, it’s clear that we’re not living in the GSCube timeline. If you look at the Wikipedia article for GSCube, you’ll see its fate is marked only by a tiny paragraph with citation needed vagueness.

According to some sources[citation needed], they were all sent back to Sony in Japan and were subsequently dismantled. They were used for prototyping visual rendering in Final Fantasy, The Matrix and Antz, as well as in a flight simulator. Although the GSCube had good rendering capability, they had a major bottleneck in connecting to external computers to transfer content[citation needed].

From what I gathered while researching, from myriad comments on forums and people wondering the same as me, Sony’s would-be wondercube did indeed never go beyond prototyping and demonstration models or enter production. Looking back at that EDGE article above, there’s a little bit in the bottom right corner of the second page where EDGE correctly assesses that Sony presupposes a desire for radical change in the movie and entertainment industry. And it would appear that a desire for this level of change died in the wake of Spirits Within’s box-office failure and uneven critical reception that seemingly doomed fully CG movies outside of Pixar and Dreamworks productions weighed in as a factor, too.

And yet, there doesn’t seem to be a defining moment that resulted in the GSCube being shelved, only speculation. It seems it faded away as the 2000s advanced just as quietly as Sony’s over-arching ambitions of the PlayStation 2 to be more than a games console and DVD player. Judging by the absence of collectors posting that they have one of these beasties, perhaps it is also true that they were all dismantled.

One possible fate is hinted at in a WIRED Nextbox article from May 2001. Here the GSCube is discussed more as a training tool for developers looking to get to grips with parallel architecture in preparation for the PlayStation 3 (then on the books for release in 2004). The SIGGRAPH 2000 presentation is mentioned, but nothing about its promise of real-time e-cinema and changing the world of CG entertainment.

If I ever do learn more about the GSCube’s fate, I’ll be sure to post a follow-up article. I’d sorely love to know in more concrete detail exactly what happened. If you know where to look, its birth and first (and potentially only!) public showcase is better documented. But as for the death of GSCube? There’s no obituary beyond “Here lay GSCube, maybe this is why it died.”

The majority of research for this piece came from the ECTS 2000 discs but also:

Damn! The GSCube is something I’ve never heard of, which makes sense considering it’s very quick passing, absolutely fascinating!

Hopefully in the years to come someone out there can shed a light on what happened to this world changing piece of tech.

Though I will admit whilst reading your article I did wonder if perhaps it was your penultimate paragraph and somehow tied to PS3.

LikeLiked by 1 person