Whenever I hear talk about early open-world or sandbox games that were pioneers of the genre, there are several that always turn up in the discussion. Activision’s Hunter is one of them. So does Bullfrog’s Syndicate. Maelstrom Games’ Midwinter is another. I can see why they come to mind; they were indeed early examples of sandbox environments, and one of them attained lasting pop-culture fame. Hunter and Midwinter’s polygonal worlds felt sprawling and offered a great deal of freedom in what you can and can’t do – at least with military matters. Syndicate’s isometric ‘living’ cities offered urban mayhem on a scale unseen before, but not much else.

What if… you wanted more than just flamethrower crowd carnage, skiing around to plant C4 charges, or trying not to crash your helicopter? What if you wanted to be part of a living sandbox world that, given the opportunity, runs independently of your involvement but will react and change according to your actions? Such a game would be years away from those 16-bit days, right?

Wrong. It existed in 1991.

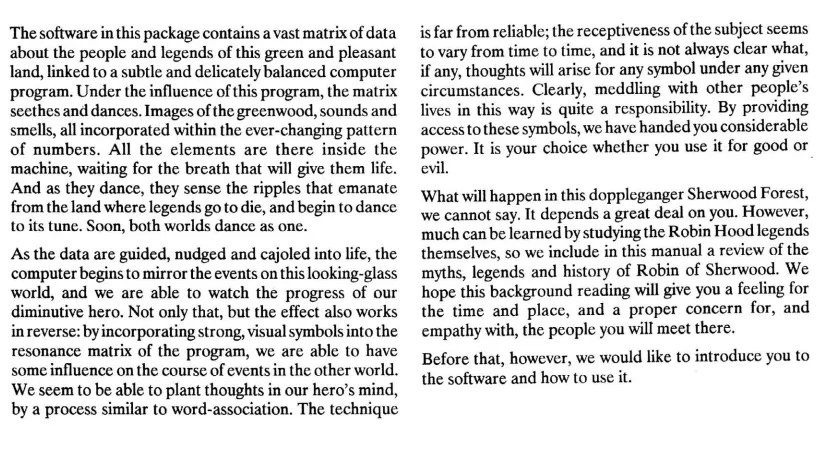

I had the idea of writing this thought piece after reading the manual for this, one of my favourite games released on Amiga, Atari ST, and DOS. A few pages in, you come across what initially felt to me like Peter Molyneux-style puffery.

I read it, showed it to my partner and then read it out in the most Molyneux manner I mustered and had a good laugh. But then I started thinking about it over the next couple of days. Yeah… yeah… I can see what they mean, why they’re so proud, why they want to show as if it’s something truly special and ground-breaking. And then the realization struck me: This charming isometric adventure game, that has its fans but has largely been forgotten, is one of the most important games ever created.

A Bold Statement?

Oh yes, it sounds like a wild one. Hyperbole, certainly. But I don’t feel it is, and hopefully, by the end of this article, you’ll come to understand why I said it.

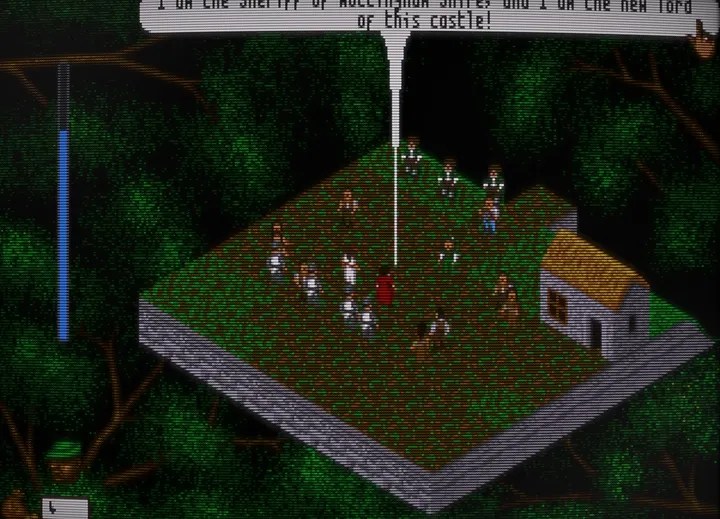

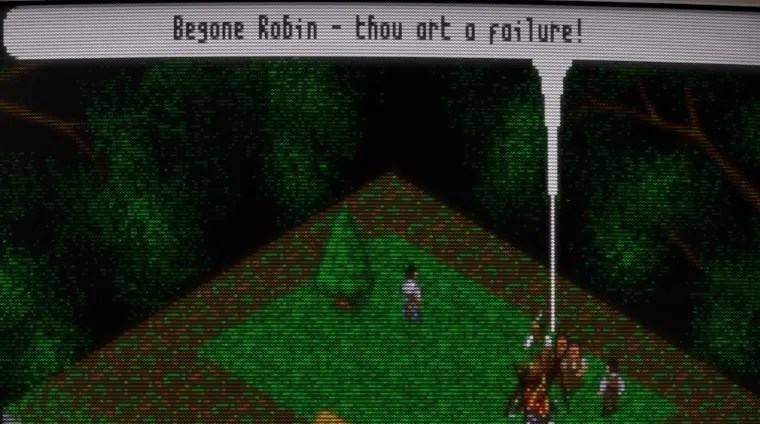

Millennium’s The Adventures of Robin Hood casts you in the role of the eponymous outlaw himself, though at the beginning he is the Lord of Loxley Castle. That is, until the Sheriff of Nottingham turns up, supposedly under the orders of the king, and turfs him out of his own castle in a charming intro that sets the scene.

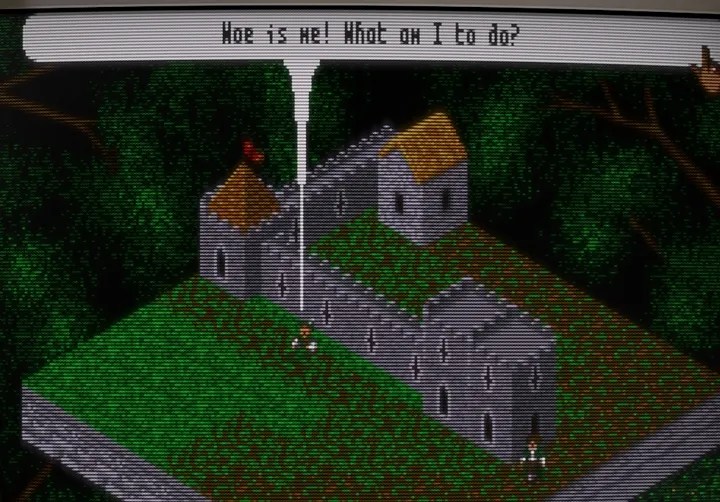

With his subjects having fled and armed Norman soldiers at the Sheriff’s side to enforce his usurpation, Robin slinks away to sit next to the castle walls and usually makes sulky or snarky remarks, waiting for you to take control as the game properly begins. And though you have an overall goal of deposing the dastardly sheriff, you’re left to do as you please.

And you can choose to do nothing at all.

If you don’t make any mouse inputs at the start or leave him be for a minute or two, Robin will then go about his daily business as he sees fit under computer control. He’ll have a wander about the surrounds of Loxley Castle; perhaps he will turn up for one of the regular proclamations signalled by heraldic trumpeting. He will indulge in a bit of archery practice at the local butts. Or, depending on his mood and how he’s regarded by the villagers, either as a hero or villain, becomes despondent and simply sits and complains. All while everyone else and the world around him carries on doing its own thing in a way that feels alive. This all takes place in real-time at a time when the majority of strategy games and RPGs were turn-based.

Now, I’m not claiming some sort of unnoticed singularity; the three dozen or so NPCs in the world are just reacting to a set of behavioural scripts as part of the Gulliver engine that the game is built on, but these come in both proactive and reactive forms and rarely feel repetitive — for good reason. Doing a little digging turned up statements from the developers that there are 1500 rules governing NPC behaviour, all focused around reputation, what Robin is doing (or not doing), the behaviour of other NPCs and the seasons of the year, and 32 personal attributes that give each person their own distinct personality. From a 1990 or 91 perspective, that’s a staggering amount of programmed game character intelligence.

A Living World

As you take part in Robin’s world, you’ll start to notice just how alive is this little sandbox Sherwood. Wealthy merchants will set up their stalls and travel between the castle and points of interest, like the church; opportunities to rob the rich and give to the poor. Minstrels will play and sing. Villagers will hunt and gather firewood, enjoy a pint at the local tavern at the end of their busy day, and gossip about you. Monks will turn up to do burials. Norman guards, of which there are six or so, will patrol around the castle, investigating the local forests for poachers. They will also pursue and arrest law-breakers should they see any, including Robin. At one point, roughly ten to twenty minutes into a game, Robin will be declared an outlaw. This adds a healthy dollop of tension, as from that point on you’re forced to sneak around and stay out of sight or take them down through swordplay or archery. A sword through the belly or a noose around the neck is your reward if you fail to do so.

Much is made of Syndicate’s populated cities, of how civilians will run away from you should you brandish a weapon in their presence, and how the police will react to your actions. But honestly, after recently revisiting Syndicate and having realized just how much of a groundbreaking achievement TAoRH is, Syndicate’s ‘living’ sandbox feels shallower and a lot less alive. Yes, there are plenty of NPCs milling about, but are they actually doing anything? Can you watch the world go by and be entertained by it?

No. But you can with Millennium’s sandbox Sherwood.

From the Source – Steve Grand Responds

I first published this article on Medium a couple of years ago. Not long after publication, I received a comment notification and was overjoyed to see that Steve Grand, co-designer, programmer, and one of the graphic artists on the game, had left one. Let’s see what he had to say:

Hi Sasha,

Someone tweeted this to me this morning and I just thought I’d write and say thanks! I’m touched.

I actually quite like the idea of being a forgotten pioneer – it means someone appreciated the things I’ve been trying to do and yet nobody needs me to go on television! 🙂

I absolutely love the thought of you reading my overblown puff in the voice of Peter Molyneux! I’d totally forgotten that I’d written it, tbh. “The land where legends go to die” is a phrase that popped into my head just the other day but I couldn’t for the life of me remember where I’d used it.

Just FYI, if you’re interested, I started out writing open worlds like this in text-only form, for education. The BBC published them as ‘Landmarks’. I actually got the idea about how to do it, technically, from watching a housefly washing its face on my computer screen (a TV set, in those days – it was the late 1970’s!), but that’s a long story…

I didn’t mean to become a games programmer at all, but I had to eat. So, after Robin I wrote a game called Rome AD92, in the same vein, and then a pretty successful game called Creatures. Now I’m doing the same thing as I tried to do in Creatures, except in a vastly more sophisticated way. That’s not a public thing yet – it’s really difficult work – but it’s coming along nicely after a decade of nail-biting effort, so maybe keep an eye out, as an historian!

Anyway, lovely article – thanks for remembering this old, forgotten pioneer 🙂

Concluding Thoughts

I’ve left the game running during most of the time I’ve been writing this article. It’s still going and things have happened. I’ve watched seasons come and go, and this digital Sherwood is still ticking along to its own pulse of virtual life. And I know the next time I put it on and leave it running, my experience will be different in both small and large ways. And that’s even before I start taking an active role and introducing my own variables into the behavioural soup.

The Adventures of Robin Hood deserves more recognition than it gets for what it set out to achieve and succeeded in doing so. Its Wikipedia article goes into detail about its achievements in living worlds and artificial intelligence, but I rarely hear it ever mentioned, let alone as being a groundbreaking title.

It deserves so much more, and I hope my passion for it goes some way to redress the balance.