This one is a real shame. I had such high hopes for Inherit the Earth: Quest for the Orb, first released in 1994 for PC-DOS and developed by The Dreamers Guild and published by New World Computing. Alas, my partner and I were both left exasperated and wanting by the end of our time with it, something that could have been so easily avoided.

Welcome to the Age of the Anthro

Inherit the Earth opens with a lovely introduction that sets the scene: humanity has seemingly vanished, but not before leaving behind inheritors: a race of sentient anthropomorphic animals known as morphs.

The backstory is told using one of my favourite literary vehicles in fiction: misremembered history. Wall paintings drawn in a style not too dissimilar to medieval tapestries with some Mesoamerican flair share tantalizing hints to how the morphs came to be – and the fate of the vanished humans.

The narrator, a character who you will meet in the game, describes some of the technological wonders (such as the power of flight) the humans possessed, and how they granted the morphs ‘Four Great Gifts’: thinking minds, feeling hearts, speaking mouths, and reaching hands – uplifting them to sentience.

And though it’s not spoken outright as the narrator muses where the humans could have vanished to (even wondering if they’d travelled to the stars, giving us another bit of worldbuilding) we’re given the impression from the accompanying painting of humans fleeing a stylized microbe that some kind of biological/viral disaster had occurred.

And that brings us to the present day for the morphs, an unspecified length of time after the collapse of human civilization. We’re introduced to the main protagonist, Rif, an orange-furred fox playing a chess-like game against a rat opponent at a country fair.

It becomes quickly apparent that the morphs have a societal and tech level akin to the high medieval period. And though they rub shoulders with many other species of morph, they all live in tribal societies delineated by those species: wolf tribe, fox tribe, rat tribe, etc, with hints of species-based racism and mistrust based on species stereotypes.

It’s here at the fair that we also get another piece of worldbuilding: the tribes rely on ‘orbs’ left behind by the humans for certain key societal functions. And it’s the theft of one of those orbs, the Orb of Storms (which accurately delivers weather predictions and tells them the best time to plant and harvest crops), that kicks off the main quest of the game: recovering the orb and clearing Rif’s name with the aid of two friends: a boar and an elk.

Isometric Emptiness

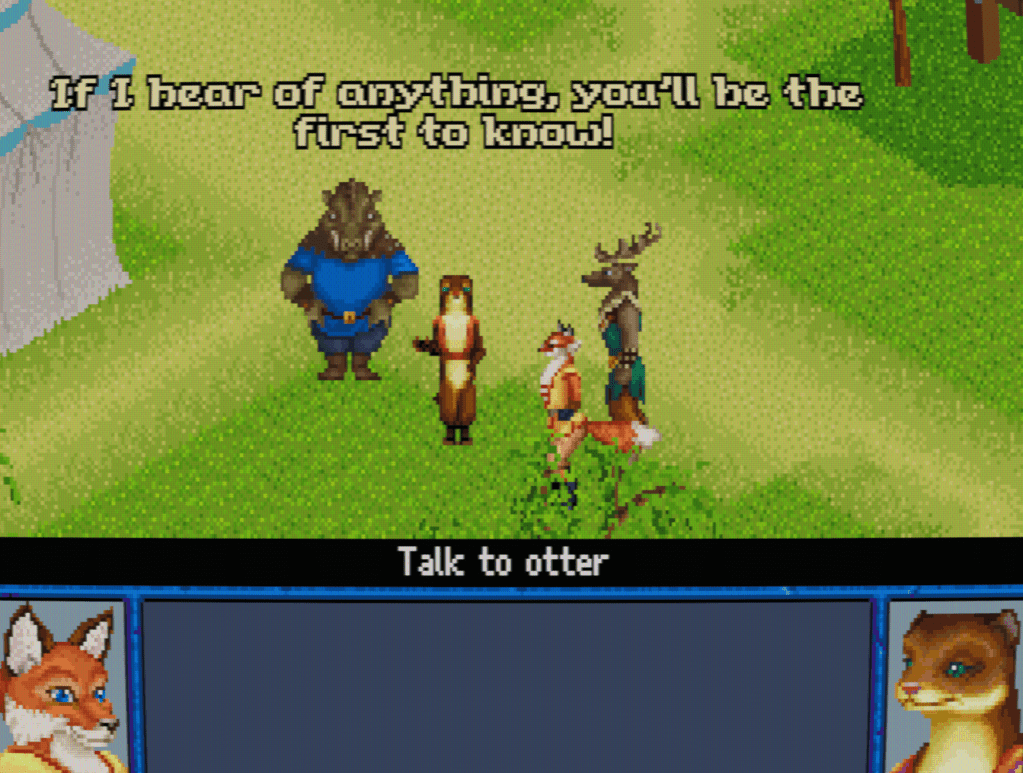

Here’s where Inherit the Earth starts throwing curveballs. The perspective will sporadically shift to isometric whenever large, open areas are presented. The first of these is the fair at which you begin your adventures, where information gathering for potential suspects and leads is the order of the day.

At first, this felt like a novel idea, reminiscent of top-down RPGs such as Ultima. And at first, it was working well enough, with numerous NPCs to talk to. But then it became quickly apparent that Inherit the Earth would not be shy about reusing identical screens with nothing in them.

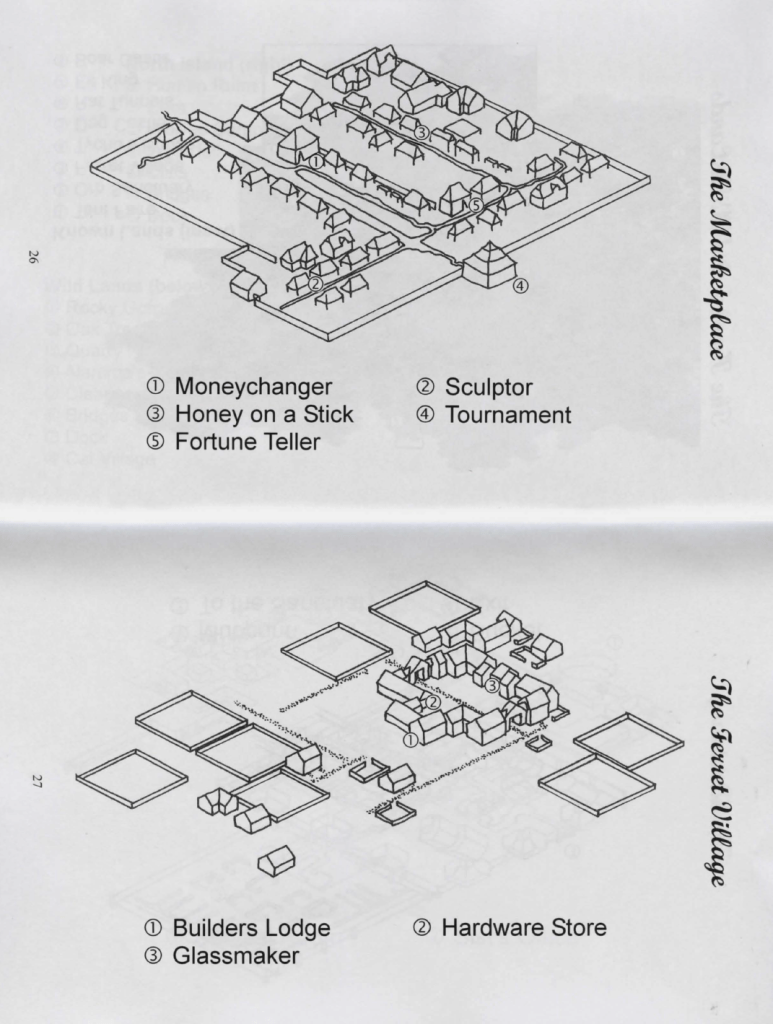

You’ll encounter this exact same room with nothing of interest inside multiple times. There are no in-game area maps either and quite a zoomed-in perspective, making even this first isometric environment feel like a bit of a maze.

Travel between areas is done via a world map, which ends up being another unfortunate example of Inherit the Earth‘s ‘a mile wide and an inch deep’ and padding-focused design philosophy. It’s lovely to look at, but it’s almost superfluous as there is nothing outside the main locations to stumble upon. No random encounters or secrets to find.

Unlike with the world maps of other point-and-click adventure games, such as those in The Secret of Monkey Island or Indiana Jones & The Fate of Atlantis, this feels more egregious in ITE as wandering around the world map takes up a significant chunk of your playtime. And promo material for the game boasts about the size of its world, but… there ain’t all that much to it beyond empty fields, awkward-to-navigate-around forests, and mountains.

The lack of depth to the exploration of its world and squandered potential for worldbuilding extends to all the isometric environments in the game. One of the worst offenders is the Ferret Village, where 85% of the sprawling isometric map is effectively featureless and, again, filled with identikit homes.

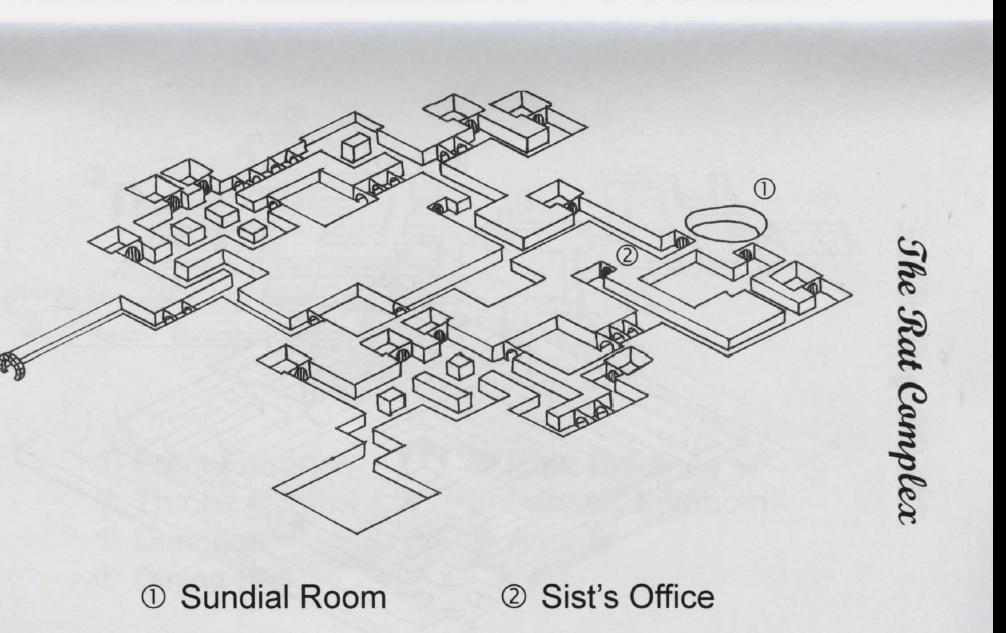

The game is very content to leave you wandering about, lost in these sprawling areas. To clue you in further, I’ll turn to the Adventurer’s Guide packaged with the game itself. It’s never a good sign when they’re giving you that for the entire game as if it’s something you’ll absolutely need.

Aside from a couple of NPCs walking about outside, the Ferret Village has only three explorable areas right there in the village centre. The rest of the homes either have locked doors or have empty, identikit rooms. And because you’re worried about missing anything on your first time through, you’ll spend way longer than you should checking every corner of the map with very little reward for your investigative efforts.

This felt like such a misstep to both me and Kit. Dreamers Guild could have populated it with colourful characters and items to look at and interact with, taking advantage of opportunities for worldbuilding and character development. But it’s just used for padding, to give you the impression that it’s a large world, albeit one hit selectively by neutron bombs.

Not helping is that Rif is, unfortunately, one of the most boring protagonists I’ve ever encountered in a point-and-click adventure game, filled with go-getter energy and voice lines, but a bit of clot when it comes to descriptiveness and displaying curiosity. Your companions, Eeah (elk) and Okk (boar), alleviate it to some degree with their own comments, but are woefully underutilized overall.

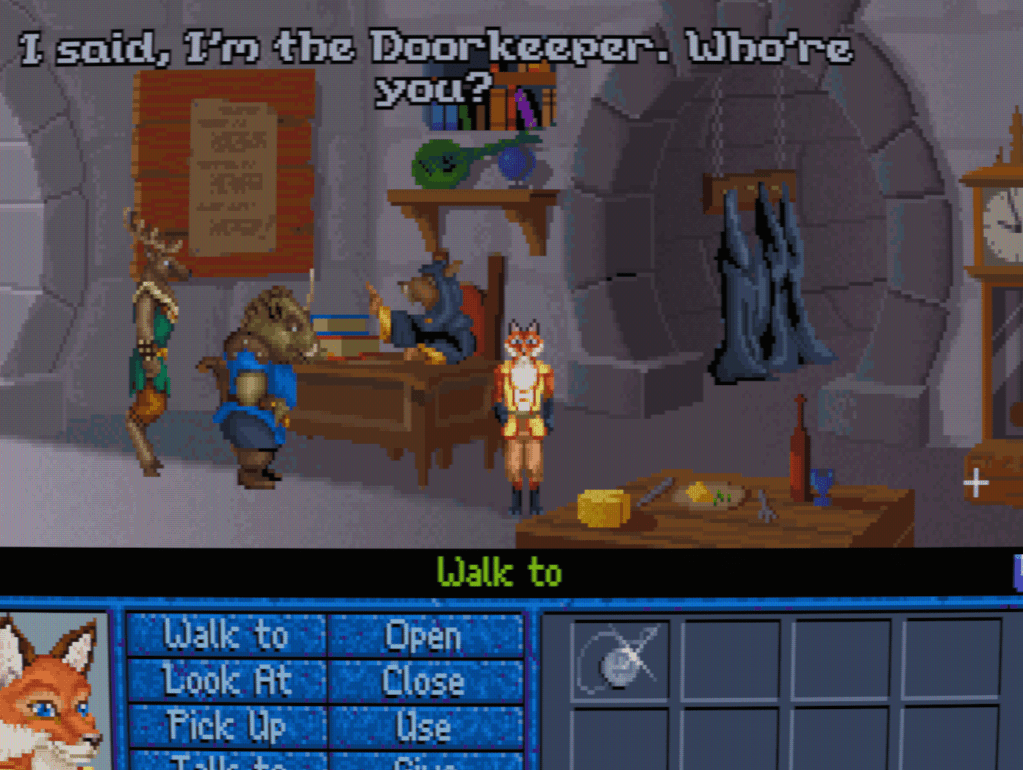

What makes it even more tragic is that when the game does focus its attention on traditional room/single-screen based adventuring and gives more unique characters to chat with and more items to examine, Inherit the Earth can be the game I was anticipating. Engaging dialogue, titbits of lore about the morphs’ technology and societies, and Rif and his companions’ personalities shining through.

You learn that the morphs have become reliant on the various orbs to give them information, some of which they can only partly understand. When the Orb of Storms is stolen, this sends them into a panic as they’ve become so reliant on it to feed themselves. The Orb of Hands seems to be some sort of voice-controlled combination thesaurus and Wikipedia that the crafting guilds have gleaned advanced designs and tools through asking the right keywords to, but in the process, may have stifled natural curiosity and experimentation, keeping them in medieval stasis. But these aspects are either only lightly or not-at-all touched upon. You don’t even learn why they’re crystal ball-shaped, despite being technological in nature; was it by design to appear to be magical artifacts?

Sigh. Did I mention yet how beautiful the pixel artwork can be, with richly detailed VGA graphics?

Just as you’re getting comfortable in those richer experiences, Dreamers Guild will yank the carpet from under your feet and land you back in its core gameplay loop: mazes.

It’s A-Maze-ing

As part of the padding out what would otherwise be a short and pretty slender experience, Dreamers Guild packed Inherit the Earth with mazes. And they’re all annoying, littered with yet more squandered potential.

You’ll learn that the rat tribe are inquisitive by nature, hoarding knowledge and books, and your quest will take you into their domain, which is, again, yet another maze. Which, okay, might be a more logical place for one. The doorkeeper will even remark about their fondness for puzzles and mazes, and have awareness of once being actual lab rats for the humans.

At first, I thought you might need to avoid the rats wandering its halls with rudimentary stealth action, lest they see through your disguise of a hooded cloak. But no, the entire area has, again, only two useful locations and identikit corridors, rooms, and NPCs wandering about that you’re unable to interact with in any way and will ignore you.

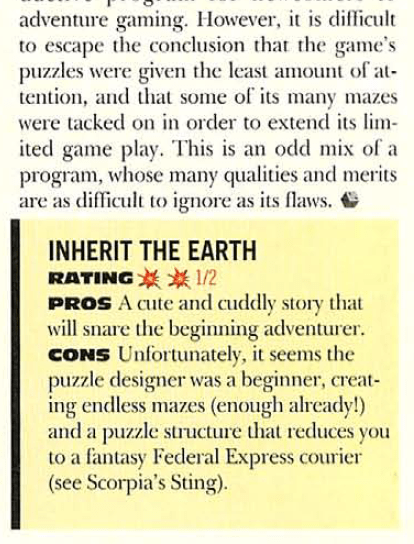

Dreamers Guild came up with a setting with a future-medieval society sporting an intriguing mix of technology, racial tension between its denizens, and then, seemingly, decided to give you as few opportunities as possible to meaningfully explore and interact with it. Even at the time, the slenderness of the puzzle aspects of the game in favour of mazes was recognized in reviews and led to some quite poor marks: 2/5 from Computer Gaming World.

The review highlighting a ‘cute and cuddly story’ also brings us to another millstone around ITE’s neck: New World Computing vetoed the game having a darker and more mature story due to anthro characters being associated primarily with children’s books, TV, and movies. So, it ends up being suitable for a younger audience with no character deaths, overall low stakes, and a cartoonishly villainous antagonist.

Thinking about it again now, the pacing of the game does bring a children’s puzzle book to mind, one where you’d have a bit of a story, then a picture to colour in, some more story, and then a maze to doodle your way through. Repeat till the end. And yet, it’s not outwardly marketed on the box as being aimed at children, and there are those remnants of a more mature story. It might explain Rif’s personality and line delivery, which can be a bit twee and almost a parody of an earnest, forthright adventurer. And yet, despite having that younger audience in mind, ITE’s narrative and puzzles do not smoothly and intuitively lead from one to another. You’ll hit a narrative or object puzzle dead end multiple times and be left wandering about the world to see if anything has changed and hoping you’ve triggered an event flag somewhere. I can’t help but feel that’s why they included the walkthrough in the game box, and we did have to turn to it several times as we became increasingly weary of the mazes and the unintuitive nature of the narrative’s trigger-flag design.

Abrupt Endings and a Confused Design

I’m not going to spoil what happens beyond what I’ve already mentioned, but I will warn that it wraps up all-too-quickly (comically so in a way that left me and my partner open-mouthed and spluttering in disbelief) and ends on something of an unfulfilling cliffhanger. This is because sequels in an Inherit the Earth series were planned, but never developed. So you’ve got a game that lays some groundwork for future titles but doesn’t do enough for itself because those other adventures might have expanded on its world and societal explorations, and mazes were the core gameplay loop.

Argh. I’m once again feeling so frustrated that even with other amazing graphic adventures on the market to look toward for design inspiration, Dreamers Guild and New World Computing couldn’t indentify the aspects that made those great examples of point-and-click adventure games, and settle on what they wanted Inherit the Earth to be without implementing a relatively poor mishmash in an effort to… stand out? I genuinely don’t know how they considered some parts of the game to be fun to play.

Closing Thoughts

I would still recommend playing it through with the game guide to hand. It’s cheap to pick up from GOG and Steam, and it’s a bite-sized experience if you avoid the padding and time-wasting to focus more on what’s enjoyable about it. And Rif’s over-eagerness ‘I’m a heroic protagonist, you know!’ delivery aside, there can be a lot of charm and fun to be found in interacting with the colourful characters that are present in the game, especially in the CD-ROM version with full-cast speech. And there’s just enough for those who enjoy technological precursor mysteries to chew on.

Inherit the Earth: Quest for the Orb actually not being all that good a game, poor reviews, and its commercial failure back in the day is explanation enough why those sequels were canned. And it might go some way to explain why two Kickstarter attempts over the last decade and change to greenlight a revival game have failed.

And yet, a continuation does exist in the webcomic that Wyrmkeep Entertainment, owner of the IP since 2002, has been publishing for many years now. There are over a thousand four-panel strips in the comic illustrated by former artists who worked on the video game, so if you’re hungry for more after you’ve played through it, there’s that at least.