“Uh, what do I do now?”

A situation many of us have been in in our gaming lives, especially with older games. Moon-logic puzzles and arcane design choices; these can leave us scratching our heads or shaking a fist at the screen.

But what if this state of frustration was sometimes by design? And not to elongate playtime for a sense of better value but to extract some extra coin from the player?

When said that way, it sounds pretty scummy, doesn’t it? Modern gaming in a nutshell, some would claim. Microtransactions and time-savers. But this is classic/retro gaming I’m referring to here, something that can do no wrong in the eyes of some.

Cluebooks and the impact they may have had on game design are something I feel have to be taken into account when discussing gaming history and the merits of older games. As do the tips phone lines run by the same companies who developed or published the games that you may feel compelled to call. But that is a can of worms that’ll remain closed… for now.

What is a Clue Book?

Game guides have evolved over the decades, now often incorporating elements we’d often associate with video game ‘art books’ such as concept artwork, bits of world lore, and behind-the-scenes information. I have a few of these, intended to be picked up and enjoyed for more than just the game information and solutions they provide.

‘Clue book’ is a term I’ve only encountered with computer games of the 80s and up to the mid-90s, and with A5-format paper booklets. After that, the glossy Prima-style guides become far more common and the use of the term seems to fade away in favour of game guides and strategy guides. But the mission goal is the same: provide comprehensive walkthroughs, maps, puzzle solutions, and additional information that will be useful to the player.

It’s that ‘additional information’ part that puts clue books on dodgy ground. The withholding of useful or vital information is something I’ve personally encountered several times in my playthroughs of classic CRPGs. It’s why I do sometimes refer to the sale of clue books as a racket. One designed to encourage the player to pay an extra $10-20 dollars back then (roughly equivalent to twice that now) on top of what they’ve already paid for the game.

Soft pressure to cough up some extra bucks will often begin immediately inside the game box or the back of the manual. Dear reader, let me introduce you to the company that kept the gears of the clue book printing presses exceedingly well-oiled: Strategic Simulations Inc.

These are all scans of the back of the manuals packed into the game box, indicating that even before a game was released, they’d already gotten the clue books ready to roll onto store shelves alongside them. It makes you wonder if they’d designed some aspects of the game around them, doesn’t it?

Okay, before we dig further into my critique and I share an example, I’ll showcase what I love about some of the clue books I’ve dug into and used in the past.

Lovely Artwork and Storytelling

The main things I look forward to when I crack open an old cluebook are some additional bespoke artwork, and if the clue book writer has taken the opportunity to spin an enjoyable narrative. These are what I regard as value added clue books. Not just bland solutions and hints as the majority of them are.

Given my dislike of SSI’s business model for clue books, you may be surprised that my first example is from Eye of the Beholder.

The clue book is introduced by famed archmage Khelben Arunsun, who frames its strategy section as the observations of a drow spy hired by the protagonist of the game. Then as you roll onto the maps and walkthroughs portion, the narrative shifts to the jottings of a somewhat hapless archeologist, Wently, and their hireling, Bennet, as they explore Waterdeep’s sewer system.

This is all wonderful stuff. My partner and I downloaded the clue book while trying to puzzle out what effect a magic item would have during our last playthrough of Eye of the Beholder, expecting only a standard one without this kind of narrative flair. And honestly, reading Wently Kelso’s (mis)adventures alongside our own ended up enriching our experience. Even if you have no intention of playing EOB but enjoy a funny fantasy narrative, I would recommend reading it through. No doubt you’ll end up feeling just as sorry for poor Bennet as we did!

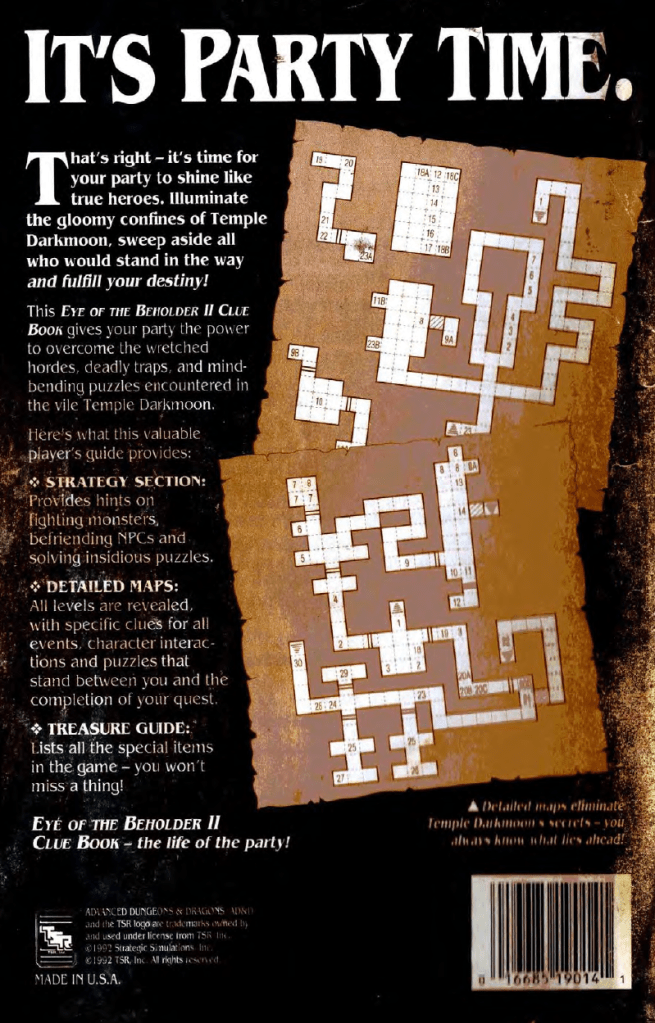

Sadly, when it came to Eye of the Beholder II’s clue book, Wently and amusing narratives were nowhere to be found. It’s another reason why I consider the first game to be the superior Eye of the Beholder experience.

Next up, we have another CRPG, one of the greats: Ultima Underworld. And with this game, we’ve got a double-whammy of goodness: there are two versions of the cluebook you can download; Japanese and English. Each with their own respective charm.

In the clue book for the Japanese release, the artwork has a cutesy style with a humorous flair. It reminds me of the little cartoons you’d often see in Dragon Magazine.

By contrast, the Origin Systems cluebook’s artwork is far more serious in nature, evoking memories of classic AD&D modules.

Ultima Underworld is a grim game in tone, so I guess the more serious nature of the artwork in the English clue book fits better? But I do so love the cheeky illustrations of its counterpart.

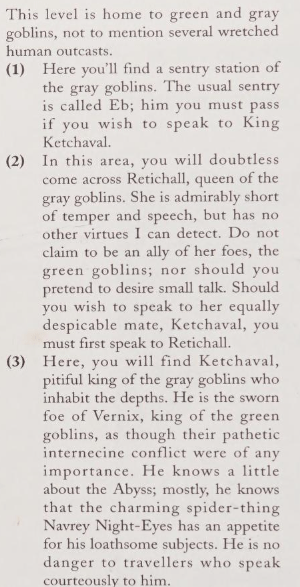

Where the English clue book wins points with me is how it too incorporates more of a narrative style in its walkthrough, framed as a letter and guidance from a foul-tempered and quite sadistic father residing in the Stygian Abyss to their child.

It’s a shame more clue book writers didn’t cotton onto the potential for additional storytelling or raising a smile or two. After all, once a player is through a game with the aid of a clue book, what is the chance that they’ll pick it up again? But if it spins a memorable and entertaining yarn, then they may do so independently, chuckling at the sour scribblings of a villainous denizen of the Abyss or at Wentley’s sewer-delvings.

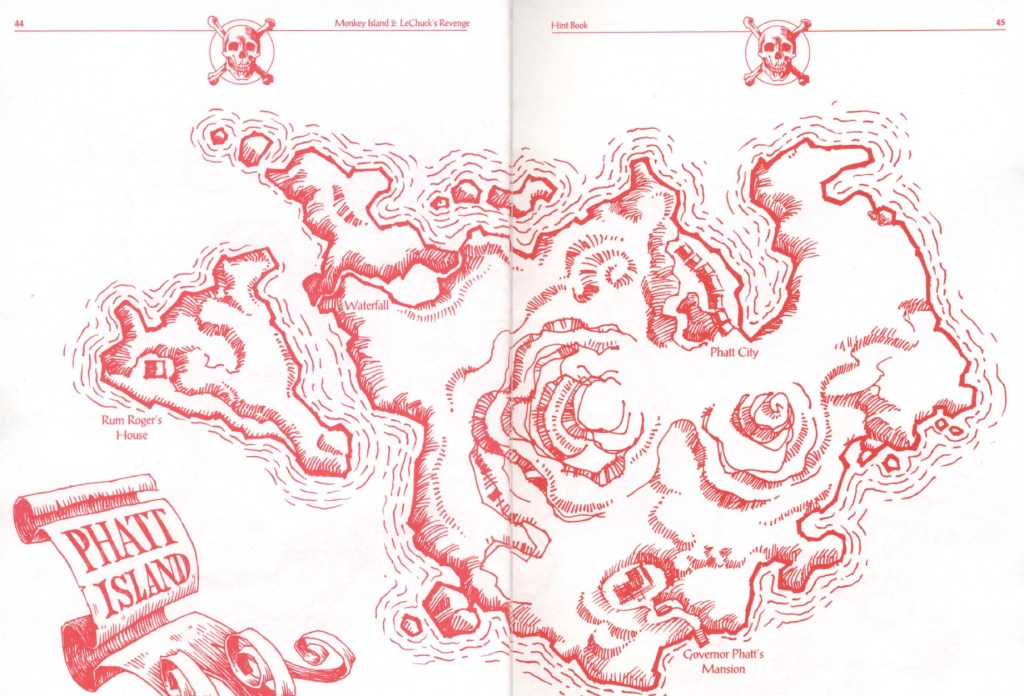

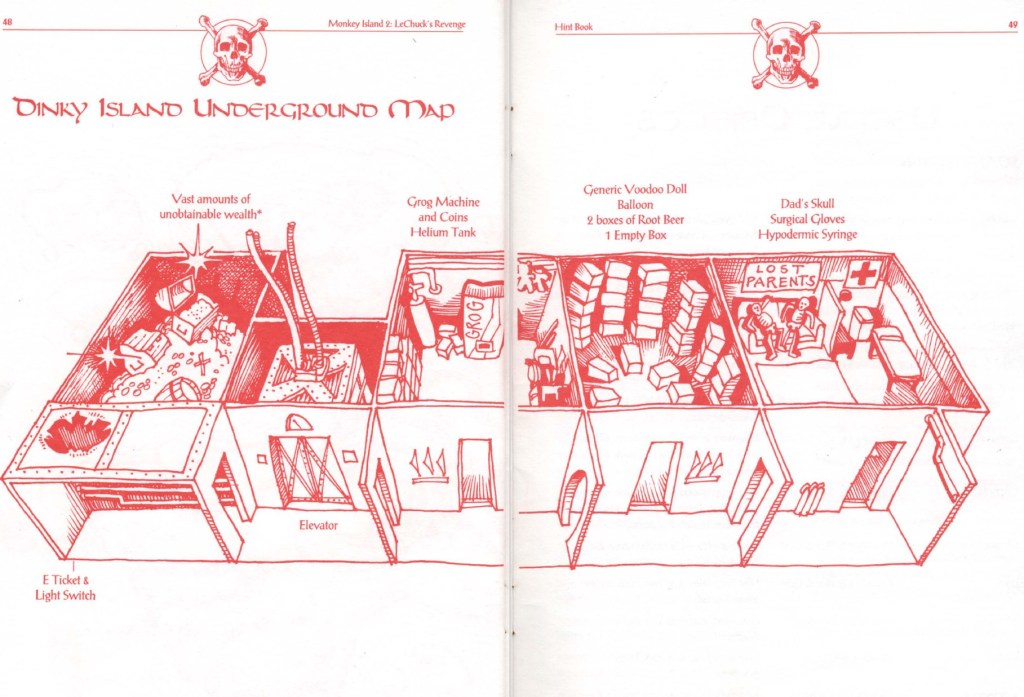

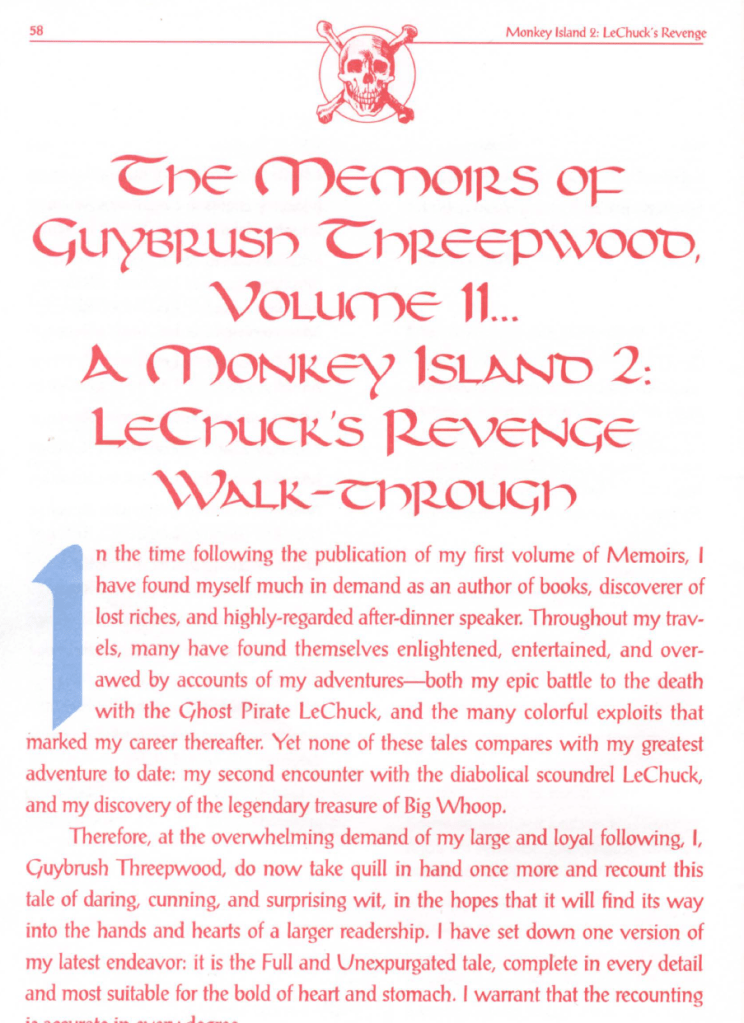

For the third showcase of value-added clue book goodness, let’s set sail for the Caribbean with The Secret of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge!

Not only do we get a gentle prod and then a more explicit guidance section for some of its puzzles, but we also get some sweet maps and an isometric perspective illustration of one of its areas! And then, just to put the cherry on the top, a narrative walkthrough of the ‘Regular’ difficulty, framed as Guybrush narrating his memoirs. Lovely stuff and again, recommended reading.

Templated Solutions & Weighty Tomes

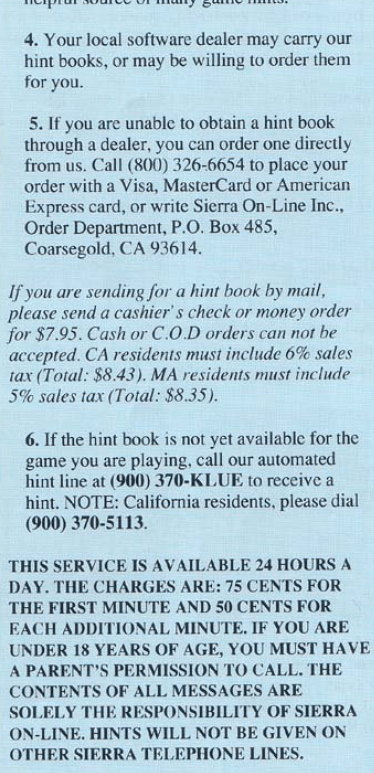

Heading over to Sierra On-Line offers us a solid example of a more standardized clue book format – with a little twist in how they presented the information so you wouldn’t get spoiled on other puzzles. They would be supplied with a strip of red film to place over the obscured solutions so you can read the text beneath.

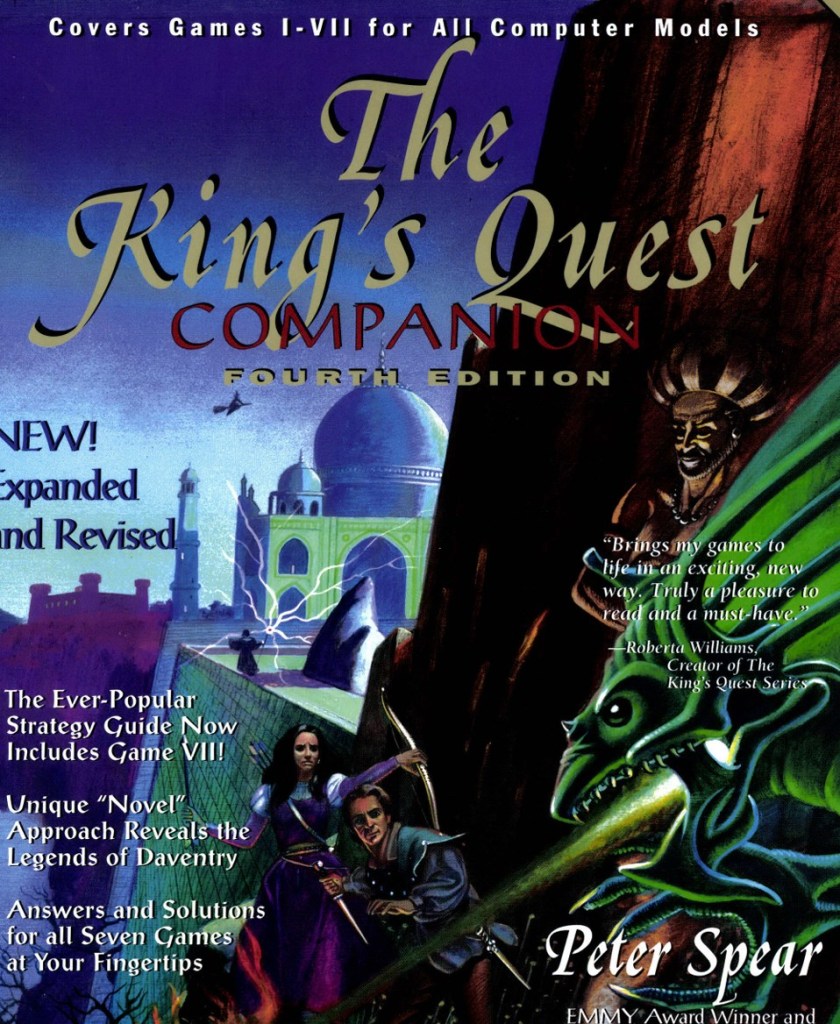

Taking a look at Sierra’s clue books also reveals one of the shining stars of value-added: The King’s Quest Companion.

I have one of these from the Roberta Williams Anthology (from memory, it’s the second or third edition) and they’re wonderful, weighty tomes. And as with my favourite kind of clue book, they incorporate heavy elements of framed narrative into their walkthroughs.

At the time, I remember being quite puzzled by the way the Companions delivered their solutions. It can make finding a quick hint for something more of a time-consuming task as you pick through the narrative and there is some inconsistency in how direct the solutions are presented (KQIV’s section in this version sheds the narrative angle) but for any fan of King’s Quest and its world, the Companions are an effective lorebook to be treasured.

Okay, Time For the Critique.

Okay, it’s time to build on my opening criticisms. It’s important to remember that even then, video games were a business. And businesses can get greedy. I feel that greed fuelled some aspects of the clue book market and by extension, hint phone lines. Let’s focus on those for a moment. I’ve not yet confirmed it to be 100% true, but I and others remember hearing that during Sierra’s boom years, Ken Williams mandated that their adventure games should include one puzzle deemed impossible by the playtesters to complete without calling their hint line. And these hint lines were not cheap to call.

With inflation taken into account, you’re talking $1.87 for the first minute of calling and then a buck 50 for each additional minute. From memory of my own experience calling a hints line in the late 90s, calls would usually end up lasting around five to ten minutes. Their expense is why we’d often get into trouble with our parents if we risked calling one when they checked the phone bill the next month.

Now, think about the outcry there’d be if one of the big AAA’s today released a game that did (or does!) something like this. And yet, this kind of practice is often handwaved away when the flaws of classic/retro gaming are raised to dispel nostalgia goggles-fuelled absolute praise for gaming’s past.

The same can be said for clue books. As lovely as Eye of the Beholder’s cluebook is, it withholds some pretty useful information not included in either the game or the manual.

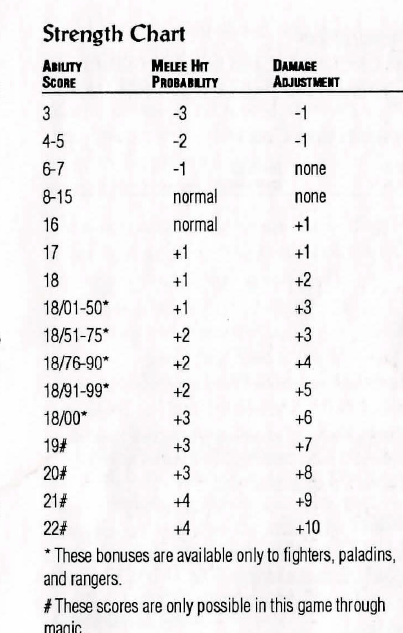

While the manual speaks in vague terms about how combat works and how higher stats are better, the strategy section of the clue book breaks down exactly how things like THAC0 work. This could easily have been included in the manual in the place of the round-about way of talking about them. If you didn’t already have a background in the AD&D TTRPG, you may be confused about all the terms – unless you bought the clue book alongside EOB.

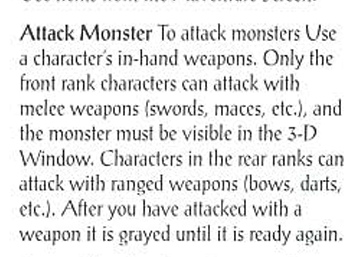

This is all that the rule book says about combat:

And for party generation:

This is a fairly soft example as the manual/rule book does give just enough information about various aspects of its implementation of AD&D’s ruleset when compared to making a puzzle impossible or at the very least extremely difficult to solve without coughing up a coin or three. But, I consider the omission of explanations of the ruleset that the game runs on to be a wilful act, leaving it confusing enough to encourage you to buy the clue book to find out just what it all means. When I first played Eye of the Beholder in 1992/1993, I was already deep into tabletop AD&D and so knew what it all meant and the kind of party mix I should aim for.

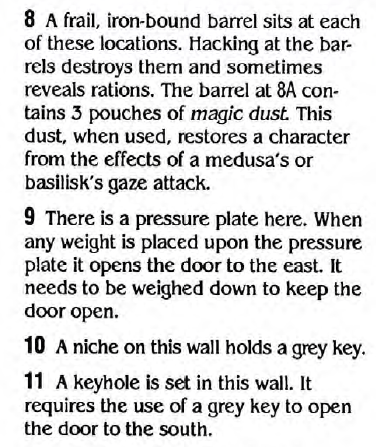

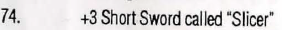

The game itself also omits information, such as just what exact bonus damage a magic weapon does; the only way of finding out is, lo and behold, in the clue book. In-game, a magic weapon will sometimes have an evocative name and will glow blue under a Detect Magic spell, but there is no way to identify them as there are in say, Baldur’s Gate. Such clairvoyance is only available to you from SSI for a handful of shiny coins.

This is pretty rife in all their CRPGs and it’s why I do consider them Chief Scallywags in the ‘Clue Book Racket’ and why special focus has been placed on them in this feature. Their games also commanded a higher price than most to begin with due to being perceived as a premium product, the equivalent of over a hundred dollars in today’s money. So to squeeze the purchaser for some extra bucks feels a wee bit greedy.

In Conclusion

I hope this has been both an entertaining and enlightening read. Clue books and hint lines and the effects they had on the industry during a time when there was little regulation of potentially predatory practices are something that has to be taken into account when recalling accurate video game history. It annoys me when I see people declare ‘video games were better when they weren’t a business’, because well, commercialism has been a part of it since the late 70s. Ever since the likes of Akalabeth were sold in little polythene bags hanging from hooks in electronics stores. And additional monetization of video games past the initial purchase is almost as old.

Clue books represent both the best and worst examples from the past of the additional monetization, potentially something to be treasured just as much as the game itself, but also a portent of the perils of industry greed.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article and would like to support me in writing more long-form features and Adventure Logs, then you can do so on my Patreon, via Kofi, or picking up copies of my digital zine, Between the Scanlines.