It’s funny how some rabbit holes open up beneath you. One moment you’re sharing an ad for Phantasy Star Online on BlueSky and intending to move on to what else you had planned. The next, you’re excitedly exploring old dead Sega-affiliated websites and sharing what you’ve found. And then sat here at ten in the evening tapping out this stream-of-consciousness piece while the buzz burns bright. But then, that is the thrill of video game history exploration and digital archaeology – and the desire to chronicle it.

Here’s the ad that opened the rabbit hole, snapped from Electronic Gaming Monthly’s February 2001 issue.

Get Connected with Sega

Before we dive into my findings, let’s give you a quick rundown on Sega and its decade-long quest to bring online connectivity to its consoles. It stretched as far back as the Mega Drive and its Mega Modem.

Released in Japan and parts of Asia in 1990 (and Brazil in 1995!) with unfulfilled plans to release it in North America as the TeleGenesis, the Mega Modem and the MegaNet service allowed for some of what we associate with daily internet use today, such as online banking and the downloading of small games. The Brazilian version also allowed for multiplayer gaming.

Some of those games would be re-released as singular or compilation carts, such as Fatal Labyrinth and Flicky. Technical issues, slow networking, and the hardware limitation of games needing to be stored in the Mega Drive’s tiny amount of RAM meant that the Mega Modem service was discontinued in Japan just two years later.

Jump ahead a couple more years and Sega launches the Sega Channel. This did reach outside of Japan and offered what was in effect cloud gaming or Nintendo’s Switch Online service for the 90s through your cable TV provider.

The Sega Saturn would also receive its own modem and online service: Netlink, released in 1996. This would allow for web browsing and also support online multiplayer in a few games, including Daytona USA and Virtual On through special NetLink editions.

That brings us to the Dreamcast and what sets it apart from these forerunners, including the oft-forgotten Apple Pippin: a built-in modem. By late 1998, interest in the Internet was skyrocketing, and Sega saw a potential avenue for the reversal of its misfortunes by offering the first console to include Internet connectivity right out of the box.

A Sega Console Online From the Start

The Dreamcast included an Ethernet port and an internal modem (33kB/s in Japan and 56kB/s in Europe and the US) as standard. Sega Chairman Isao Okawa was convinced that online gaming was the future of the industry – something that Japan lagged far behind in compared to the US, Europe, and Korea where the likes of Ultima Online, Starcraft, and Lineage were busily establishing themselves as online play juggernauts. Japan’s first PC MMORPG, Lifestorm, had proven to be a moderate success, but its player base was dwarfed by those of its peers. Chairman Okawa knew that only an online-orientated console would usher in Japan’s online gaming revolution and if he played his cards right, it would be Sega leading the charge.

Unfortunately, not everyone at Sega was convinced. When Okawa approached developers creating the earliest games for Dreamcast and pitched online connectivity as a core feature, most were sceptical. It would fall to an unassuming puzzle game, ChuChu Rocket, to lead the charge as the Dreamcast’s first online-play-focused game.

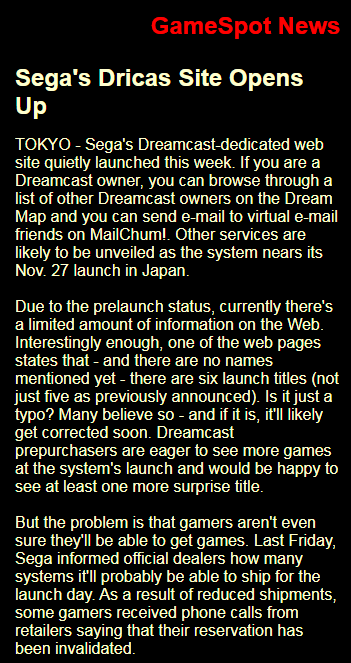

So, now that they had a Dreamcast and a handy Ethernet cable, how did people actually get online to play ChuChu Rocket? Well, first you had to wait until the end of 1999 for the game to be released. Although the Dreamcast launched with its modem and port all ready to be plugged in, there were very few things at first you could do online with it. The Dricas service, established by ISAO Corporation to offer a handful of admittedly neat online services such as video chat with the DreamEye camera, went live via a website before the release of the Dreamcast, as reported in this article on a Wayback snapshot of the Gamespot website from 1998.

It would be another year before Chairman Okawa’s vision of offering an online gaming powerhouse would taxi to the runway for takeoff.

Now disembarking: J-Data and Free-DC

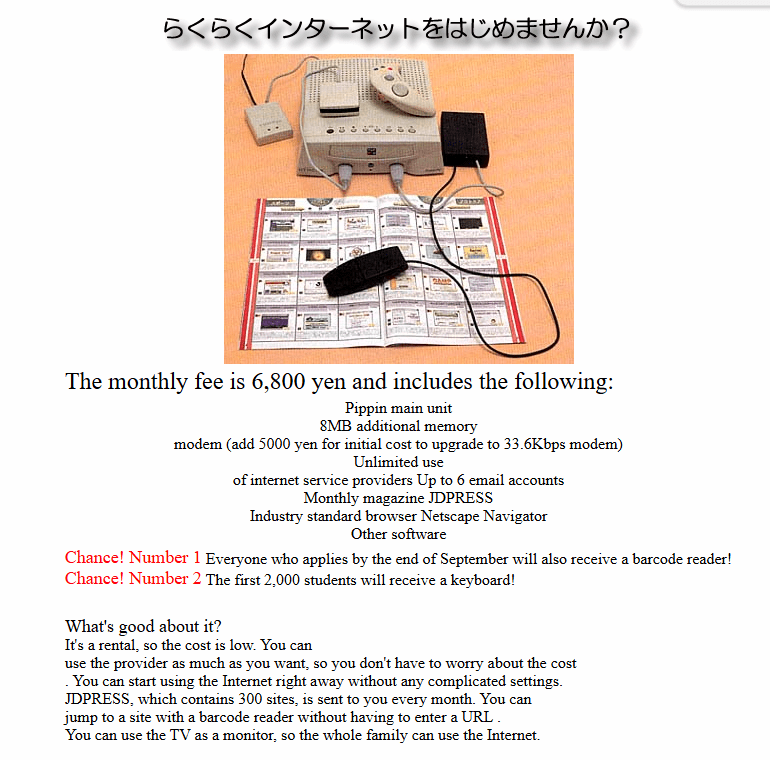

Telecommunications company J-Data has a history when it comes to supporting online services for consoles. It was J-Data that had supported the short-lived Apple Pippin console a few years earlier that, looking at a scrape of their website, now feels like it served as a dry-run for what they’d do for Dreamcast.

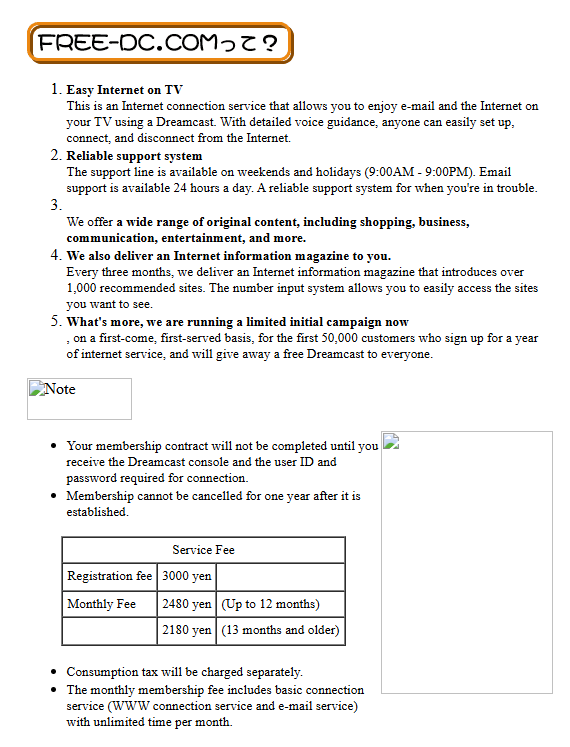

For Dreamcast, they’d establish Free-DC, a dedicated Internet Service Provider (ISP) that, honestly, sounds like the name of a scam website to get a free console.

By paying a monthly fee to J-Data, you’d be able to access Dricas, the wider Internet, and play games online; something crucial for Sega’s killer app online game: Phantasy Star Online.

Fees are pretty reasonable for the time, 2480 yen, especially when this includes unlimited access. For the first 50,000 people who signed up for the service after launch, a free Dreamcast was included as part of signing up for a one-year contract. You also received a quarterly magazine with a directory of recommended internet sites. Kind of like a phone book for the internet. Imagine that.

One thing you’ll read about in this history of the Dreamcast is that Chairman Okawa, who would later go on to save Sega from ruinous debt by loaning the company a large sum of money and then forgiving their debts to him (if a portrait isn’t enshrined in Sega’s HQ and bowed at every day, there should be), also personally paid for a year of free internet access to be bundled with every Dreamcast. So convinced was he that the future of the company and Dreamcast lay in online gaming. I’ve not been able to pin down exactly when he did this, and I presume this only included Japanese Dreamcasts, but it’s reported history and worth mentioning. If I do pin down some firmer details, I’ll update this article with them.

Enter, Reem-Chan

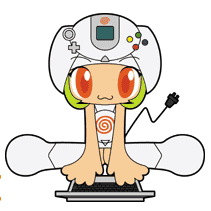

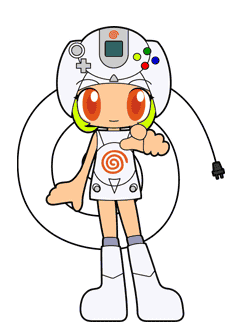

Okay, now we get to the heart of the matter and what captured my own attention and that of quite a few people on BlueSky when I shared images and details of her: Free-DC’s mascot, Reem-chan, created by Mari-chan of the TINAMIX Project.

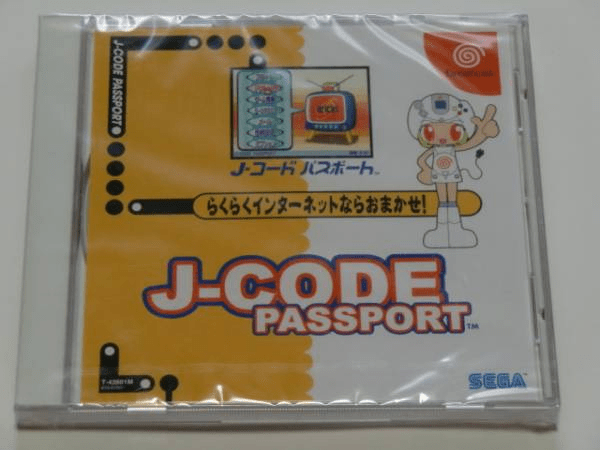

Just look how cute she is! Reem appears on the service website and also on the cover of the J-Code Passport disc used to access the service.

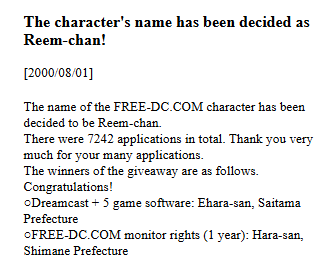

Reem/Reem-chan was the name bestowed upon the previously nameless mascot by the winners of a competition held by J-Data.

Well done, Ehara-san and Hara-san! I hope you enjoyed your free Dreamcast and free year of net access.

Closing up the Rabbit Hole

That’s all I have to report about my impromptu diggings into this fascinating bit of Sega and console history. It’s a shame this all didn’t pan out as well for Sega as hoped, especially when compared to Sony’s bumbling-in-comparison efforts at online connectivity for the PlayStation 2. And it’s clear that Microsoft was watching and taking lessons from Sega’s efforts when designing the Xbox – something that may be another bitter pill to swallow for those who feel Xbox also helped hammer the nails in the coffin that Dreamcast and the Free-DC service sadly ended up sharing.

One thought on “Reem-chan and Okawa’s Dream: The Y2K Dreamcast Online Future Personified”